Bavarian Illuminati

The Bavarian Illuminati was an Enlightenment-era secret society founded May 1, 1776. Originally called the Order of the Perfectibilists, "its professed object was, by the mutual assistance of its members, to attain the highest possible degree of morality and virtue, and to lay the foundation for the reformation of the world by the association of good men to oppose the progress of moral evil."[1][2]

After the Elector of Bavaria, Charles Theodore, banned the association with the encouragement of the Roman Catholic Church in 1785, many theories began to circulate concerning the survival of the organization and their alleged aims. Following the French Revolution, conservative writers who favored the French Ancien Régime began publishing pamphlets which claimed that the Revolution was the result of Illuminati infiltration of French institutions, in particular Freemasonry. Professor John Robison in Proofs of a Conspiracy claimed that French Freemasonry had been infiltrated and subverted by Weishaupt's Illuminati and transformed into a revolutionary organization.[3] In his Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism, Abbé Augustin Barruel, a French Jesuit Priest, also alleges an Illuminati connection to the Revolution.[4]

The conspiracy theories circulated by advocates of the old French aristocracy and monarchy would eventually arrive in the United States and feature in the sermons and writings of Jedidiah Morse. While George Washington wrote that he did not doubt that the "diabolical tenets" of the Illuminati had spread to the United States[5], Thomas Jefferson called Barruel's claims of conspiracy "the ravings of a Bedlamite" and described Weishaupt as "an enthusiastic Philanthropist". "[Weishaupt]", writes Jefferson, "is among those...who believe in the indefinite perfectibility of man. He thinks he may in time be rendered so perfect that he will be able to govern himself in every circumstance so as to injure none, to do all the good he can, to leave government no occasion to exercise their powers over him, & of course to render political government useless."[6]

A paradox frequently commented upon by investigators of the Illuminati is how an organization which seemed to represent classical liberal notions of freedom, justice and universal brotherhood should become synonymous with tyranny and elitism. The preface to an English translation of Baron Adolph Knigge's Practical Philosophy of Social Life may shed some light on this. In it, the translator records that although the organization could have "proven beneficial to the world" few of its members were "animated with that heroic disinterestedness and self-denial" which their philanthropic aims required. Although the Illuminati was composed of the "greatest geniuses of all ranks and countries", "ambition and other passions soon began to undermine the fabric; caballing traitors abused the power which the society possessed, to revenge themselves upon their enemies, or to satisfy their thirst for dominion and wealth."[7] This last characterization more closely resembles the "Illuminati" featured in modern-day conspiracy theories.

History

The Bavarian Illuminati was founded by Adam Weishaupt in 1776.

Modern influences

Even without evidence of a survival post suppression in 1785[1], and despite the seemingly positive aspirations of the society, some claim that the organization survived and is part of a conspiracy.

Connections

Jesuit Order

In 1755, at age seven, Adam Weishaupt began his formal education in a Jesuit school.[8] After Pope Clement XIV’s suppression of the order in 1773, Weishaupt would become the first layman professor of canon law at the University of Ingolstadt.[9] The position had been held by a Jesuit for the previous 90 years. Weishaupt would later model his own secret society on the Jesuit society's hierarchical structure.

Along with Jews and pagans, ex-Jesuits were not considered worthy candidates for initiation into the Illuminati.[10] The Minerval Academies disseminated anti-Jesuit material, published in Munich at their own expense, and Illuminati professors were commissioned to obtain the expulsion of any Jesuits found in their institutions.[11]

Although the Jesuits were considered enemies by the Illuminati, Adolph Knigge, a high-ranking member who later became disillusioned with the group, accused Weishaupt of "Jesuitism" and believed him to be "a Jesuit in disguise".[12]

Knights Templar

Both the Knights Templar and the Bavarian Illuminati have been accused of orchestrating the French Revolution. The Paris Temple, which had formerly been the Templar Keep, housed the ousted Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. In 1314, the French monarchy put the Grand Master of the Templars, Jacques de Molay, to death for alleged heresies. Charles de Gassicour, author of Le Tombeau de Jacques Molay (1796) claimed that at the moment of the king's execution by guillotine a member of the crowd rose up and exclaimed, "Jacques de Molay, you are avenged!"[13] Augustin Barruel addressed Freemasons directly in his Memoirs, writing "Yes, the whole of your school and all your lodges descend from the Templars...To the preexisting code of impiety they added the vow of vengeance against kings and pontiffs who had destroyed their order..."[14]

Skull and Bones

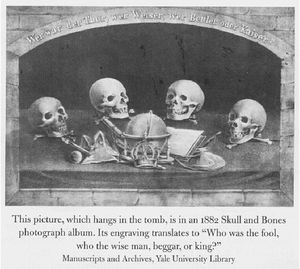

The Yale senior society Skull and Bones is also known as "Chapter 322". Historian Antony Sutton has speculated that it is the 322nd chapter of the Bavarian Illuminati.[15] The existence of a German chapter of Skull and Bones is affirmed by an anonymous article written by an infiltrator into their headquarters on Yale campus. In a satirical essay titled "The Fall of Skull and Bones" published in 1877, the infiltrator describes the interior of the Skull and Bones "tomb". It includes "an old engraving representing an open burial vault" with four skulls laid inside which is accompanied by a card on which is written, "From the German Chapter. Presented by Patriarch D.C. Gilman of D. 50". Above the vault is a German engraving which translates to, “Who was the fool, who the wise man, beggar or king?” This parallels the Bavarian Illuminati initiation ritual in which the initiate is presented with a human skeleton and asked if it is the skeleton of a king, a nobleman or a beggar.[16]

Zoroastrianism

In Fire In the Minds of Men, James H. Billington writes that "Zoroastrian-Manichaean fire worship was central to the otherwise eclectic symbolism of the Illuminists".[17]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 McKeown, Trevor W. A Bavarian Illuminati primer.

- ↑ Mackey, Albert G. (1966). Encyclopedia of Freemasonry. Macoy Publishing. p. 474.

- ↑ Robison, John (1798). Proofs of a conspiracy against all the religions and governments.... Philadelphia: Printed for T. Dobson, N°. 41, South Second St., and W. Cobbet, N°. 25, North Second St.

- ↑ Barruel, Augustin (1794). (book) https://archive.org/details/MemoirsIllustratingTheHistoryOfJacobinism. Missing or empty

|title=(help) (German) - ↑ http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mgw/mgw2/021/1820176.gif. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://memory.loc.gov/master/mss/mtj/mtj1/022/0000/0057.jpg. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Knigge, Adolf, Freiherr von and Will, P. (Peter) (1805). Practical philosophy of social life. Lansingburgh, Penniman & Bliss, O. Penniman, printers, Troy.

- ↑ Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie Vol. 41, p. 539

- ↑ Engel, Leopold. Geschichte des Illuminaten-ordens. Berlin: H. Bermühler Verlag, 1906, p. 33

- ↑ Chapter III: The European Illuminati, from New England and the Bavarian Illuminati, by Vernon L. Stauffer Ph.D., 1918

- ↑ Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism, p. 586

- ↑ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07661b.htm

- ↑ Templars: History and Myth: From Solomon's Temple to the Freemasons, p. 265

- ↑ Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism, by Augustin Barruel, 1797, p. 213

- ↑ Sutton, Antony C. America's Secrets Establishment Order of Skull&Bonnes (book).

- ↑ Illuminati Prince Degree.

- ↑ Fire In the Minds of Men: Origins of the Revolutionary Faith, by James H. Billington, 1980, p. 95